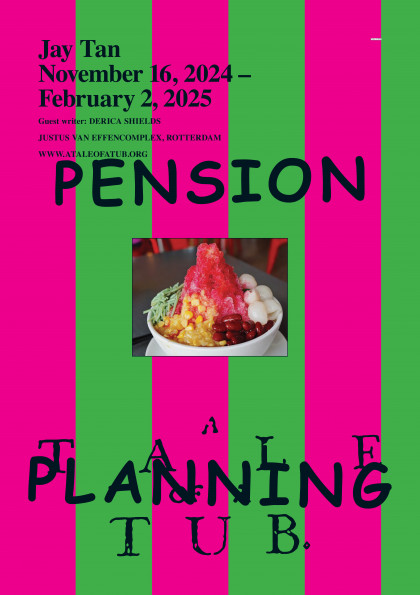

Pension Planning

JAY TAN

November 16, 2024 – February 2, 2025

Guest writer: DERICA SHIELDS

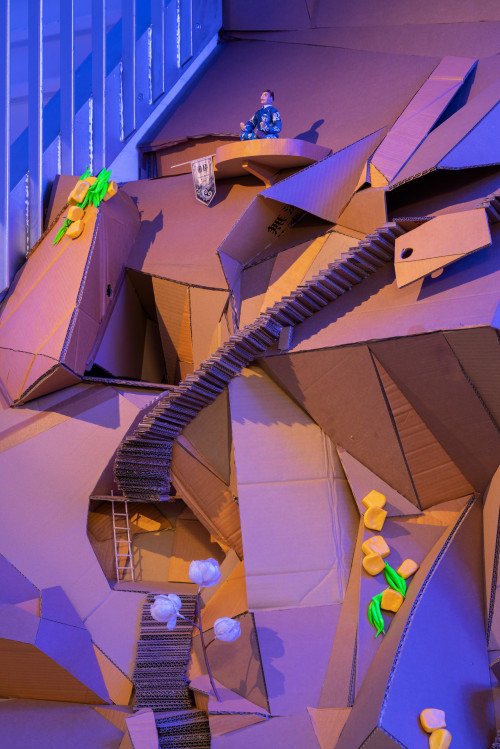

Muddling through misunderstandings of macroeconomics, Pension Planning begins with the daunting task of climbing a mountain. Approached through the D-I-Y decorative aesthetics of high-school art class, YouTube videos and kinetic cardboard crafts, the exhibition stands as a kind of visual slang, in which the symbolic, sacred, stereotyped, systematic and silly are blended together into a three-story diorama.

Navigating these inclines, which literally span the three floors of our building, we climb through Tan’s attempts to meld an unwieldy visual and linguistic lexicon. As the topography unfolds, they morph reconstructions of fragmented cultural references ranging from confusing-maybe-racist images, longed-for traditions and validating personas. The delay and distortion of Asian diasporic nostalgia is an intergenerational dialogue reluctantly translated by bilingual cousins—an ‘Ornamentalist’ [1], made-up, megalith-y glossary, born of a blunt application of fake-it-till-you-make-it.

Off the back of this, within the social landscape of ageing populations and countries that ‘get old before they get rich’—where government bonds and investment funds call into question whether ethical communal welfare funds could or ever did exist—this exhibition metaphorically postures towards the task of saving for retirement, a mountain often impossible to climb. Prompted by their own parents’ difficulty retiring, and tethered to spending time alone as an adult in Malaysia—where their father hails from— Tan has been trying to understand and reconsider practices and responsibilities of ancestral worship and filial duty. When the material realities of pension planning come into play, this intergenerational dialogue (with both the living and the dead) is not just a tool of self-definition, or cultural investment, but a lived necessity.

In being confronted with the challenges of ageing and money, and at the same time learning about how much work ancestral worship can be, Pension Planning plots out the tension between financial and spiritual well-being, one born from the diasporic reality of clumsily teaching oneself your culture (in the face of another’s priorities), where rituals pull from the past and present simultaneously—think, a votive filial offering of the latest Lexus mini-van.

[1] Anne Anlin Cheng, Ornamentalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Events

Tuesday, January 21, 2025, 7:00 – 9:00 PM

Vengeance of the Phoenix Sisters at KINO Rotterdam

Saturday, November 16, 2024, 5:00 – 8:00 PM

Exhibition Opening: JAY TAN: Pension Planning

Thursday, March 13, 2025, 6:00 – 8:00 PM

Pension Planning Practicalities: An Introduction to financial planning for freelance and other arts workers with PETER VAN DEN BUNDER, CHRIS RIJTEN and JAY TAN

Biographies

JAY TAN (1982) is an artist working across sculpture, performance, sound and video. Working with everyday household materials as well as D-I-Y approaches—such as home craft techniques of self-taught mechanics—Tan creates worlds in which cultural vernacular is both interrogated and rewritten. Decoration as aesthetic rubble. Through these processes, they are trying to figure out how the history of British Colonialism (in Malaysia specifically) brought their parents together and influenced their worldview. Born in South London, now based in Rotterdam, they completed the MFA at the Piet Zwart Institute in 2010, were a 2014/15 resident at the Rijksakademie and currently teach at the Masters of Artistic Research programme at KABK, Den Haag, and the Fine Arts Department at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, Amsterdam.

DERICA SHIELDS is a writer and editor from London. She works across disciplines with a particular focus on Black aesthetics, cultures and epistemologies. Her oral history project A Heavy Nonpresence gathers seven Black Londoners’ accounts of the British welfare state and was published by Triple Canopy in 2021. She was a 2022–2023 artist-in-residence at Jan Van Eyck Academie where she developed ‘Given to Cottons and No Silk’, a two-channel video installation. Her book Bad Practice, which considers the potentials of Black failure, is forthcoming from Book Works.

Alternative Interest(s)

By DERICA SHIELDS

Maybe because she is my big sister and she wants me to learn, finally, how to save, or maybe because we have been passing the same €150 back and forth these past few months, the artist Milktooth suggested we set up a pardna. We hadn’t thrown pardna before, but we knew that it worked because, after moving to Britain from Jamaica, our elders pooled their money using this rotating savings scheme to buy houses and to send for the children they’d had to leave behind. Each month, members of the pardna paid the same amount to the ‘banker’ who would then disburse the money to one member. This continued until every member had received a draw. The first member to draw essentially receives a loan while the final member has saved.

Like hungamento di sam, kalbas, kasmoni and susu, pardna is a form of mutual aid thought to have been carried by enslaved Africans and adapted to their circumstances in the plantation economies of the Americas where European colonists were birthing more brutal forms of property, such as mortgaging land and slaves for credit. After abolition, some formerly enslaved people used similar arrangements to buy land. A few genera- tions later, when West Indians came to the UK from the late 1940s, the same banks that were founded to provide credit for Britain’s slave economy refused Black people loans. If they did lend to our elders, they charged extortionate interest rates. On this leg of migration, too, they returned to the pardna system.

Milktooth and I struggled to come up with a group of people to throw pardna with, feeling our communities too fragmented, or geographically and economically disparate to sustain trust. We also discovered an impulse to be rigid when flexibility would better serve our aim, and that we had to keep pushing back against capitalism’s false corollary that stability equalled trustworthiness. I briefly diverted us by trying to turn the pard- na into a get-rich-quick scheme, to get more money out than we were putting in. But if we entered the conversation questioning our capacity to trust ourselves and others, we came to understand the pardna as a relational technology that might help us create, strengthen and deepen the community we want and need.

MILKTOOTH: Was there an amount you wanted to save up specifically, or for anything specifically?

DERICA: An apartment deposit, also for the artist visa application fee. I also would like a new winter coat [laughter]. I just want to have some structure for saving. If I could save €500 I’d be happy.

Well, we could start small.

Is that small?

I was thinking €4000.

Wow! Well, then we should involve other people, because there’s no way we’ll get to €4000 by ourselves.

Who?

Family’s not a guarantee. You can’t pressure a Jamaican elder for money [laughter]. I’m trying to think of personality traits.

Trustworthy?

Trustworthy, reliable, steady? I mean, I’m not steady which is why I need something like this.

Yeah [laughter].

I hate when you agree with me when I’m being self-deprecating!

I feel like I don’t know no one that hard. You know what I mean? I don’t tend to build tight friendships with a lot of people. I have a very small group. We’d have to trust people to stick around and put money in after they draw. Because the motivation leaves after you draw.

That’s why I should draw last [laughter]. What if it’s pairs? Each person contributes separately but one member of the pair draws in the beginning and the other at the end.

Ohhh, so the accountability is there. But if they’re married, one household would be putting in double, because they’re still participating as individuals…

I don’t mean pairs like spouses necessarily, but people with close relationships: siblings, friends, roommates. Like if you were at the beginning of a pardna and I was at the end, I’d trust that you’d continue to pay because I’m your sister. We depend on the relationships.

Maybe it’s a good idea to have guarantors for backup. Or we draw up a contract?

But then it becomes like everything that I’m not enjoying about the Netherlands where finding a house or a studio becomes showing a panel of six people your portfolio. How do we ensure that relationships grow as a result of this, rather than remain transactional? If we join with people in our age group and in our circumstances, freelancers with multiple jobs, we can build in a flexibility that will make us all more able to honour the commitment. What if January is a month off from throwing pardna because UK freelancers pay taxes in January?

Okay…

Or one pardna membership can be used by two people who alternate payments between them to ease the strain if they need to. Maybe the freelancers make a unit with a salaried person.

Oooh! Then they split the draw or work out what percentage they’re each getting. I like pairing with the salaried workers to support freelancers. Are you for or against a contract?

I’m for an agreement that we create together. I’m anti a contract that’s about recourse to law.

Got ya. As a group, we decide on the circumstances that someone gets an emergency draw rather than ‘you’re not doing what you agreed so let’s go to court.’ Nice.

So we have two types of pairs now. The first type is two individual members who get two draws: one early and the other draws towards the end. The second type shares one membership between them and they draw once; that’s the freelancer and salaried person.

The pairs can be one person who we know well with a person we don’t. We get more people into the pardna who we don’t know.

We need a contingency fund. The first month’s hand could belong to the banker. Everyone puts in and the banker holds it until the whole pardna is over.

So a deposit? [laughter] But then we stand to lose the deposit. I guess that’s where the trust has to come in. Because one person might be crying over something someone else would respond to like, ‘buck up and be an adult.’ We should discuss the circumstances that would lead to the opening of the contingency fund.

Anything that leads to a sudden loss of income or capacity to work. But the pairing structure can help because if you have a life-changing event at week five but you’re due to draw in week eight…

You can wait.

[Laughter] This really brings out the inner prison guard!

For real, I’m such a fucking prison guard! Only joking. The contingencies are bereavement, job loss, partnership breakdown, life-changing illness or health crisis. Wait, I forgot that people usually pay to get into the pardna.

And that’s the contingency fund?

That’s probably the contingency!

S*an [D. Henry Smith] suggests that each month a portion of the draw is split between members. So, if the draw is €1000, then one member gets €800 and the rest split the remaining €200. Everyone gets ‘a little lunch money’.

This is something we can discuss as a group as well, because we all have something to lose if someone flakes. Maybe it’s the people who are most trustworthy who go first. That’s not a great thing to say out loud.

And the appeal of the pardna is that it doesn’t penalise you for not achieving stability in a system that forces you into precarity—the way credit scores do. Someone who is unstable on paper might need the first draw loan to pay off a debt that’s collecting interest. That doesn’t mean they’ll abandon the pardna. The assumption that people with fluctuating incomes are the most likely to renege on their promise is part of the thing we have to go against.

Also, if we each know what we’re saving for, we can be communally responsible for us each achieving our goal. You’ll draw in June because it’s your birthday. I’ll draw in October because I come to the end of a job contract. You want to get in the habit of saving, this is a structure that can help you, where we can all encourage one another. Doesn’t matter what you’re saving for. I might internally judge you [laughter] but it doesn’t mean that we’re not helping each other.