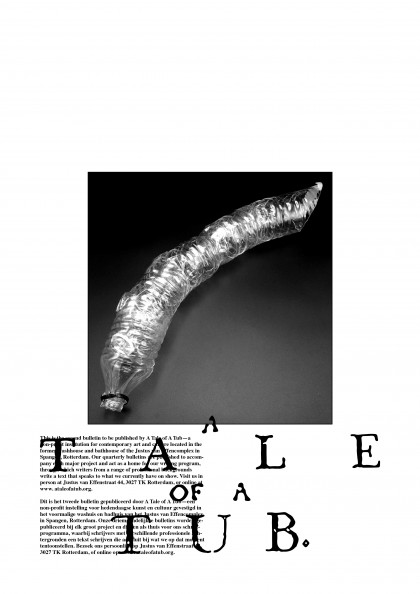

Installation view of Patty Chang: Glass Urinary Devices at A Tale of A Tub. Photo: Gunnar Meyer.

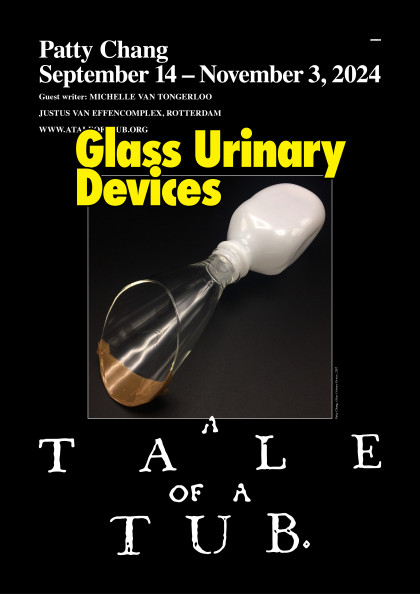

Glass Urinary Devices

PATTY CHANG

September 14 – November 3, 2024

Guest writer: MICHELLE VAN TONGERLOO

In 2015, American artist Patty Chang followed the South-to-North Water Diversion Project, the longest aqueduct in the world, which brings water from southern to northern China. While walking, she collected her urine in discarded plastic bottles found along the way, drawing a connection between the large-scale infrastructural attempt to control the flow of water and the uncontrollable flows of her own body. Once back in Boston, Chang made a series of hand-blown glass sculptures modelled on the plastic bottles that she utilised during her journey. For Chang’s exhibition at A Tale of A Tub, a collection of these prosthetic-like sculptures will be presented on the ground floor, reflecting on the flow of water that once passed through the former washhouse alongside Chang’s own ruminations on water as a metaphorical point of departure for geopolitics, human excess and waste.

The question of public sanitation sits very much on the surface of many Dutch cities—highly visible on the one hand, and eternally lacking on the other. Depending of course, on where you sit on the gender scale. As an example of this, at the end of the nineteenth century, the first ‘pee curl’ was installed by the Public Works Department of Amsterdam—a spiral-shaped steel urinal structure designed for men to pee in private in public, many of which are still standing today. A couple of decades later in 1928, the nation’s capital established its first urinary committee titled ‘Committee of Consultation on the Urinal Question in Amsterdam’. Yet despite this civic investment in managing sanitation health, the male-to-female ratio of public toilets has been historically skewed, with claims that women’s toilets involved higher costs and that public toilets were intended for ‘the man who works in the street’ being waged in the face of complaints. Off the back of this, in 1969 the Dutch feminist group Dolle Mina campaigned for women’s ‘pee rights’, a ‘potty parity’ push that has continued right up until this day—brought to even more public attention in the last ten years when, in 2015, Geerte Piening urinated in the street and refused to pay the fine in protest, a refusal that saw her go to court and the issue enter mainstream attention. Just this year, in response to public lobbying, €4 million has been pledged to installing wheelchair and gender accessible public toilets throughout major cities. Yet still now, it’s hard to walk down the centre of Rotterdam on a busy weekend without only encountering a portable urinal installed for man’s convenience.

The body and its confrontation with the realities of access has long underpinned the work of Patty Chang. Most known for her video and photographic work from the mid 1990s, through which she focused on the performing female body, her more recent works unpack the geographical and environmental realities of locations of political, cultural and personal significance. While a notable turn, bodily fluids continue to flow through her work, from urine to breast milk to tears. Here, Chang’s glass urinary devices almost act as a hinge between her early feminist expressions and her later mediations on landscape—given their awareness of the gendered body and the limits to access it rubs up against within the public realm. Within the context of the Netherlands and the aforementioned history of public sanitation, Chang’s series of sculptures, not coincidentally made from translucent glass, push at the visibility of our daily encounters with problems of access, both within the domains of public health and beyond.

Accompanying the exhibition is a specially commissioned text by Rotterdam street doctor and general practitioner Michelle van Tongerloo. In this text, Tongerloo reflects on the realities of women’s homelessness and sanitary care in the streets of Rotterdam. It will be published in our second bulletin—a newly established platform for a corresponding writing program, which experiments with different ways to talk about the content of our exhibitions.

Events

Saturday, September 14, 2024, 5:00 – 8:00 PM

Exhibition Opening: PATTY CHANG: Glass Urinary Devices

Thursday, October 17, 2024, 6:30 PM

Access Toolkit for Artworkers:

A Talk with IARLAITH NÍ FHEORAIS

Publications

Bulletin 2/2024

by Michelle van Tongerloo

Patty Chang: Glass Urinary Devices

Glass Urinary Devices

Patty Chang

Biographies

PATTY CHANG (1972) is a Los Angeles-based artist and educator known for probing taboos, stereotypes and cultural myths. Born from her performance practice and regular inversion of being both behind and in front of the camera at once, Chang frequently appears in her own work, investigating complex aspects of Asian identity by, for example, impersonating contortionists and legendary street fighter Bruce Lee, while simultaneously testing the limits of female representation and social acceptability. Her most recent works explore landscapes impacted by large-scale human-engineered water projects, such as the Soviet mission to irrigate the waters from the Aral Sea, as well as the longest aqueduct in the world, the South to North Water Diversion Project in China. Chang’s work has been exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Guggenheim Museum, New York; New Museum, New York; BAK – basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht; the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; M+ Museum, Hong Kong; and the Moderna Museet, Stockholm, among others.

MICHELLE VAN TONGERLOO is a general practitioner and street doctor in Rotterdam. From her clinic in IJsselmonde to working as an independent doctor at Pauluskerk—where she provides care homeless, addicted or undocumented people—she links major social issues to the harsh reality of her consulting room.

Maria

MICHELLE VAN TONGERLOO

At work I need to use the toilet, really badly. It’s the end of a busy day at the Pauluskerk where I work as a street doctor with homeless people, and I postponed going to the toilet for a long time — now I can’t wait any longer. The key to the staff toilet is lost, shit.

So I’ll have to use the public toilet. As I close the door behind me I hear some rummaging. A male visitor to the church is also sitting on the toilet and talking to himself while fumbling through some bags. Cans, papers and other things fall in my direction and suddenly I hear him getting up. I get a bit scared. Does he want his stuff back? Will he stand on the toilet seat to peep over the cubicle? I get up and quickly put on my pants. No matter how badly I have to poop, I can’t do it now.

This encounter seems too trivial to mention, but for me it was a moment of realisation. How something seemingly normal, going to the toilet in private, is out of reach for homeless people. And still, this is nothing: try changing your sanitary towels in the bushes. Or toilet paper rather, because you can’t afford sanitary towels. Then you try to steal it in the toilet of a restaurant, which is very difficult, so you walk around with red stains on your trousers.

After the failed visit to the toilet I wait for Maria. She was proud to have managed to find a permanent outdoor place to sleep and I promised to walk with her to her place of residence after work. While I wait in front of the church, I see many of my patients walking down the street: the Pauluskerk has just closed and visitors must leave. Some are sitting on benches, some are lying on the grass, while others wander along the quay. One by one they are summoned by law enforcement: move on, don’t sit, don’t drink—unless you can pay for it, on a terrace.

In 2008, the municipality of Rotterdam presented the ‘City Lounge Strategy 2008-2020’. This sounds exactly as it was intended: the city centre should become a space for the purchasing public to chill, shop and drink cocktails. ‘We are creating a city centre which will be a showpiece and that will form the stage for a large part of the urban economy’, as can be read in the introduction. Public space as a commodity: companies and shops must be supported so that people primarily behave as consumers. Undesirable elements, such as the homeless and pigeons, obstruct the desire to spend money and must therefore be kept out of the city. Hostile architecture supports the strategy.

Bus shelter benches are replaced by lean bars to create less comfortable seating. Remaining benches are fitted with so many armrests that you can’t lie down on them. Chairs become narrower and in certain spaces the ground is made uneven. Iron spikes, which are placed on roofs to keep pigeons away, are now being placed on the ground to keep homeless people away too. Waste bin tops are closed off so it becomes difficult to search through them.Hostile architecture takes on many forms, but is consistent in its purpose: to ward off that which is ‘unwanted’.

‘Hey doctor!’ Maria shouts from across the road when she sees me. She walks over looking cheerful. She has been living on the streets since she was eight years old. Born in Hungary, she came to the Netherlands through many detours. For work, she says. But I honestly don’t think that is going to happen. After years of surviving outdoors, she has become addicted to the streets.

Image taken by Michelle van Tongerloo during a street visit, 2024.

Nowadays I have adjusted my strategy for supporting people. When people first end up on the streets, it usually takes a while before they fully realise that they are homeless. They continue to look for work and take care of themselves in the belief that it will eventually work out, and it is during this period that people can be helped most effectively. Then, eventually, the shame of being homeless and the accompanying sense of worthlessness sets in. People give up, their brain changes due to the survival mode they are in, and after a while the strength needed to fight your way out disappears. That is why I now, if someone has been on the streets for less than three months, I have good hope that I can quickly guide them back into ‘the system’. I prefer to put people in the safety of a hotel immediately, and guide them back into the system from there. After three months the success rate drops considerably and I have to find other ways to support them.

As we walk to her home, Maria talks incessantly. It is mostly in Hungarian, but somehow I understand most of what she says. We take the Mauritsweg to the Nieuwe Binnenweg and I still have to use the toilet. But when I ask restaurants if I can use theirs, I get refused. This is presumably because Maria is standing next to me. Her clothes are dirty and full of holes, she talks non-stop and has no teeth: they are probably afraid that she will scare off customers.

As we walk towards the Museum Park, she points out restaurants which sometimes give her food. The sushi there is highly recommended, she says, that lunchroom over there not so much, and while she lists reviews of places to eat, she checks under the tops of trash cans to add cans and bottles for deposit to her bag. I decide to help her, but I am much less adept at it. She finds eight cans on the short route; I only find one.

‘Look, there I live’, says Maria, smiling with pride. When I see her sleeping place, I have to keep myself from laughing: Maria sleeps next to hostile architecture, which is intended to keep people like her out. The bridge from the Museumpark to the Kunsthal is blocked at the bottom with different uneven stones, to ensure that homeless people cannot hang out and sleep there. But that does not mean that you cannot lie down next to it, as Maria does. Brilliant, and deeply sad at the same time.

If this architecture doesn’t achieve its purpose, then all it does is send a signal to people that they are unwanted. Why wouldn’t we rather invest in humane architecture, where people like Maria can still have some privacy? That wish is a utopia. Our heavily gentrified city is moving in a completely different direction and is being politically modelled on the wishes of wealthy citizens.

In 2004, the first year that Leefbaar Rotterdam was on the council, a major campaign was launched which carried the slogan: ‘Support him with care, not with cash’. Through this, people were encouraged not to give money to beggars. The lives of homeless people have become increasingly punishable: it’s prohibited to beg, it’s prohibited to stay in the same place for too long, it’s prohibited to drink in public, it’s prohibited to urinate in public, it’s prohibited to sleep outside.

Homeless people do all of these things—what else can they do?—and then they get fined. Especially in recent years there has been an extreme development in Rotterdam: police and enforcement officers issued 1,500 fines in 2023, twice as many as in the rest of the Netherlands. In 2018, there were 150 fines. In 2018, sleeping outside was only fined 71 times, since 2021 this has increased rapidly, peaking at 716 fines in 2023. The number of fines for alcohol abuse shows a similar picture: from 67 in 2018 to 645 in 2023—an increase of 900 percent. Fines for disruptive behavior even increased by 9,500 percent.

But they often cannot pay the fines they receive. This sometimes results in even higher fines and sometimes in a prison sentence. After serving the sentence, the original fine remains, so the homeless person can be thrown back in prison at any time. People who urgently need help are being held hostage by the system. The first thing I do when I’m home: use the toilet.

Patty Chang, Glass Urinary Device (QM43, Amber Half), 2017, hand-blown borosilicate glass, plastic and tape, 22.8 x 7.6 x 7.6cm. Photo: Gunnar Meyer.

Patty Chang, Glass Urinary Device (QM01, Shoe with duct tape), 2017, hand-blown borosilicate glass, plastic and tape, 28 x 8.2 x 8.2cm. Photo: Gunnar Meyer.

Installation view of Patty Chang: Glass Urinary Devices at A Tale of A Tub. Photo: Gunnar Meyer.

Patty Chang, Glass Urinary Device (QM03, Chute), 2017, hand-blown borosilicate glass, plastic and tape, 48.3 x 7.6 x 7.6cm. Photo: Gunnar Meyer.

Installation view of Patty Chang: Glass Urinary Devices at A Tale of A Tub. Photo: Gunnar Meyer.

Patty Chang, Glass Urinary Device (QM04, Lil white funnel), 2017, hand-blown borosilicate glass, plastic and tape, 26.6 x 6.35 x 6.35cm, and Patty Chang, Glass Urinary Device (QM02, Shovel with masking tape), 2017, hand-blown borosilicate glass, plastic and tape, 21 x 7.6 x 7cm. Photo: Gunnar Meyer.

Installation view of Patty Chang: Glass Urinary Devices at A Tale of A Tub. Photo: Gunnar Meyer.

Patty Chang, Glass Urinary Device (QM35, Triple Spout), 2017, hand-blown borosilicate glass, plastic and tape, 48.3 x 17.8 x 19.1cm. Photo: Gunnar Meyer.

Installation view of Patty Chang: Glass Urinary Devices at A Tale of A Tub. Photo: Gunnar Meyer.

Patty Chang, Glass Urinary Device (QM36, High Tower), 2017, hand-blown borosilicate glass, plastic and tape, 83.8 x 8.9 x 8.9cm, and Patty Chang, Glass Urinary Device (QM45, Large double), 2017, hand-blown borosilicate glass, plastic and tape, 36.2 x 9.5 x 9.5cm. Photo: Gunnar Meyer.

Installation view of Patty Chang: Glass Urinary Devices at A Tale of A Tub. Photo: Gunnar Meyer.

Installation view of Patty Chang: Glass Urinary Devices at A Tale of A Tub. Photo: Gunnar Meyer.

Patty Chang, Fountain, 1999, single-channel digital video (colour, sound), 5 min 30 sec.